Introduction

Some international colleagues have talked about the general interest in Finland’s good PISA results and asked me to give a presentation to the subject. So, I decided to investigate the topic, which is talked about all over the world, and to share this knowledge with others.

OECDa (n.d.) defines PISA as follows: “PISA is the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment. PISA measures 15-year-olds’ ability to use their reading, mathematics and science knowledge and skills to meet real-life challenges.” (OECDb n.d.) Measurements have been done every three years. 79 countries and over 500 000 young people have been involved during last measurements.

The tool gives an opportunity to the countries to compare their results with others and with the average. The previous PISA measurement results are from 2018. The latest PISA measurement was held in 2022 and the results will be published by the end of 2023. (Ministry of Education and Culture n.d.)

PISA Results of Finland compared to Other Countries

Even though Finland has the reputation as an excellently performing education-friendly country, the PISA meters have been swinging somewhat down recently. In 2018, the measurement focused on literacy as it did in 2000 and 2009 too. Finland is among of the top OECD countries, but the reading literacy results are declining. There is the same phenomenon in the most OECD countries. (Ministry of Education and Culture n.d.)

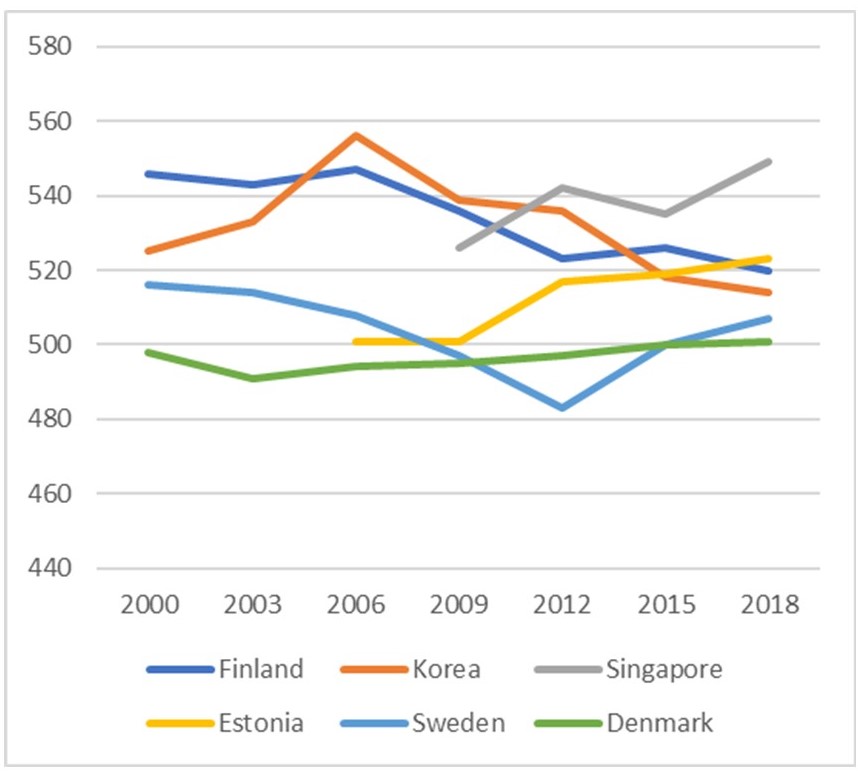

In 2006, Finland’s PISA reading scores peaked at 547 points. Since then, scores have steadily declined, reaching 520 points in 2018. Korea’s score trend is somewhat like Finland’s, but the difference between the starting and peak levels is more pronounced. Finland’s neighboring countries Denmark, Sweden and Estonia have been below Finland in literacy measures in the 2000s, but in recent measures their performance has been positive, with Estonia surpassing Finland’s score in 2018. In the most recently published measures, Singapore was by far the best performer (Koulutuksen tutkimuslaitos, n.d.).

Picture 1 PISA literacy score averages in some countries in 2000–2018 (Koulutuksen tutkimuslaitos, n.d.)

The graph (Picture 1) shows the literacy score averages of six reference countries for the period 2000–2018. The countries are Finland, Korea, Singapore, Estonia, Sweden and Denmark. Finland’s curve is flat between 2000 and 2006, ranging is varying between 540 and 550 points. Since 2006, Finland’s performance has been mostly negative, with a score dropping to 520 in 2018. Korea’s literacy scores rose from 525 (year 2000) to 556 (year 2006) in six years. Since then, the score has moved almost in line with Finland. Singapore’s scores have been available since 2009. At that time, the score was 525, from which it has risen in steps to reach 550 points in 2018. Denmark’s score has risen steadily and moderately from 2003 to just over 500 points in 2018. Between 2000–2012, Sweden’s score decreased in almost the same proportion as Finland’s, but the starting level of points was lower than Finland’s. In recent measurements, Sweden’s score has risen sharply and ended up being just under 510 points in 2019. Estonia’s curve has not fallen at all since 2006. After a period of steady progress, the country’s reading scores have risen sharply, with the most recent reading score crossing the 520 points thresholds.

Comparing Finland to Other OECD Countries

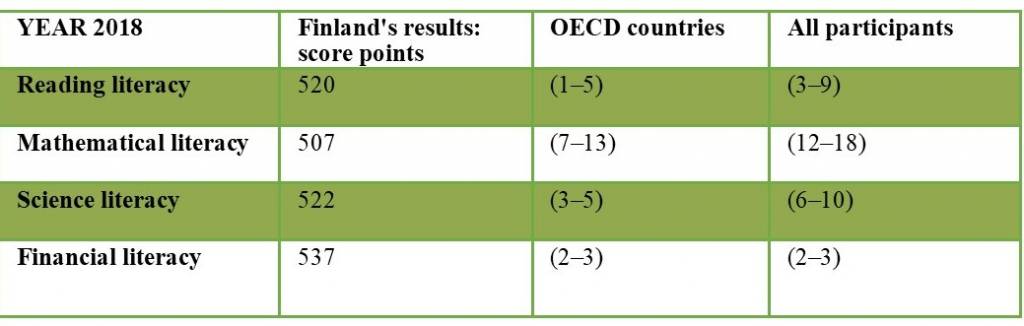

Nevertheless, when having a look more closely at the PISA results in 2018, the development cannot be interpreted as alarming. Picture 2 shows Finland’s PISA score points and rankings against OECD countries and all participating countries. Finland scored 520 points in the Reading Literacy section, ranking between 1 and 5 among OECD countries and between 3 and 9 among all countries. Mathematical literacy score points were 507 and with this result Finland ranked 7–13 in the OECD and 12–18 in all participating countries. Science literacy score points were 522: ranking 3–5 in the OECD and 6–10 in all participating countries. Financial literacy score points were the highest at 537. With this score, Finland ranked 2–3 among OECD countries and 2–3 among all countries.

Picture 2 The PISA results of Finland in 2018 (Ministry of Education and Culture, n.d.)

In reading and in financial literacy, Finland is one of the tops in the world. Also, mathematics and science literacy ranking are more than satisfactory. The success of Finnish school children in PISA has been explained by the carefully developed education system and the work of highly educated teachers. (Cheng 2019; Opettajien ammattijärjestö 2019).

One can see the effects of equal society behind the result. In Finland, the performance gap between schools was the smallest in the PISA measurement in 2018. The differentiation of learning outcomes between schools have been prevented quite well and the high-quality neighborhood schools are respected. For example, high performance in literacy correlated with a high satisfaction with life. (Minister of Education 2019.)

“School is a cornerstone of the Finnish welfare state. Regardless of a person’s background, school guarantees everyone an equal opportunity to learn the skills they need in life. In a rapidly changing world, Finland’s strongest competitive edge comes from a high level of knowledge, skills and competence, and schools that enable everyone to learn the skills they need in life” (Minister of Education, Li Andersson, 2019).

How to Improve on Rather Good Results

In Finnish public discussion, you can hear both proud and concern comments related to the PISA. When analysing the results more closely, it has been found that the performance gap between pupils has increased. Learning outcomes are affected by the family background more and more. Pupils, whose parents’ educational level is the lowest, have the biggest falls in skills. Also, girls are performing clearly better than boys and, in general, the students have more negative attitudes than before. It looks that the pupils needing for help are not supported the same way as before, even though changes in educational financial resources have not been found. The decline of skills has been partly explained by the growing number of pupils with an immigrant background. Regional equality and variation between schools has increased, and the gap between rural and urban schools had grown in favour of urban schools. (Kirjavainen & Pulkkinen 2017; Minister of Education 2019.)

The teachers’ union of the country has stressed that the increase in the number of pupils with low reading skills is because many of them have not received enough special support for their learning. Resources for learning support must be rapidly increased to improve the situation. In other words, there is not enough special education. Also, the differences between municipalities’ special education resources are significant. The other concern is that although teachers are still conscientious and competent in Finland, their burnouts have become more common. At the same time, the attractiveness of the teaching profession has been decreasing. (Opettajien ammattijärjestö 2019; see also Cheng 2019.)

Improvement visions have also been released. It has been announced in many arenas, that the reading should be more valued in the country. Lately the Government has aimed to reduce learning gaps and increase educational equality by, for example, extending compulsory schooling and launching specific action programmes. (Minister of Education 2019.) The quality of education must still be improved, and the educational level of future age groups raised. The impact of socio-economic background can be prevented by paying attention to learning difficulties earlier, through high-quality early childhood education and care. The same individual support must continue throughout comprehensive school, for example by ensuring enough special education. (Opettajien ammattijärjestö 2019.)

Focus on the Big Picture

As a representative of social policy and social work, I would also like to look at the bigger picture. The Finnish education system and society are undergoing major structural changes. Global factors influence education policy and its direction, including in Finland. In recent years, the relationship between education and the economy has been emphasised in political decisions. In addition, the negative effects of the Finnish recession of the 1990s are still being felt in the Finnish welfare state. This may have an impact on the well-being and educational success of children and young people. An uncritical reflection of one country’s education system will not have the desired effect, and it makes no sense to copy the educational structure of one country to another. Global, political and environmental factors are increasingly influencing education. Education policy must be made in relation to the historical choices and current educational and administrative systems of each country. (See Cheng 2019).

Education policy must be made in relation to the historical decisions and the current education and administrative system of each country.

I conclude that in Finland we can be proud of the education system and the welfare state, the current situation, and the history. Nevertheless, we should never stop critically analysing what are our main goals for the future. We should also clearly articulate the values and practical implementation of the policies and administrative strategies behind the education system. When practices and developmental steps are concretised and explained so that everyone can understand them, we can really define where we want to go and later evaluate how and why we ended up where we did.

The article is based on the lecture at the Global Sessions which is a specialized event for social and health degree programmes, organized by Marie Cederschiöld Högskola together with a wide network of universities. My visit to Marie Cederschiöld Högskola in 29.5–2.6.2023 was funded by Erasmus+ Higher Education Agreement (Staff Mobility for Training) and Tampere University of Applied Sciences (TAMK).

Sources

Cheng, J. 2019. PISA and Global Education Policy. Understanding Finland’s Success and Influences. Boston: Brill Sense.

Kirjavainen, T. & Pulkkinen, J. 2017. PISA-tulokset heikentyneet huippuvuosista – kuinka kuinka paljon ja mistä se voisi johtua? Talous ja yhteiskunta, 45(3), 8–12. Read on 28.5.2023. https://jyx.jyu.fi/bitstream/handle/123456789/55549/1/ty32017kirjavainenpulkkinen.pdf

Koulutuksen tutkimuslaitos [Finnish Institute for Educational Research]. n.d. Tiivis yhteenveto PISA2018-tuloksista. Read on 28.5.2023. https://ktl.jyu.fi/fi/pisa/pisa18-esite-verkkoon.pdf

Minister of Education. 2019. Minister of Education Andersson on the PISA results: In Finland, the school closest to your home is among the best schools in the world. Press Release 4.12.2019. Read on 28.5.2023. https://okm.fi/-/opetusministeri-andersson-pisa-tuloksista-suomessa-oma-lahikoulu-on-maailman-parhaimpien-joukossa?languageId=en_US

Minister of Education. n.d. Finland and Pisa. Read on 28.5.2023. https://okm.fi/en/pisa-en

OECDa (n.d.) How Does PISA Work? Read on 28.5.2023. https://youtu.be/-xpOn0OzXEw

OECDb (n.d.) What Is PISA? Read on 28.5.2023. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/

Opettajien ammattijärjestö [Trade Union of Education]. 2019. OAJ Pisa-tuloksista: Oppimistulokset saadaan nousuun lisäämällä opetusta, erityisopetusta ja vahvistamalla opettajamitoitusta. News. Published 3.12.2019. Read on 28.5.2023. https://www.oaj.fi/ajankohtaista/uutiset-ja-tiedotteet/2019/oaj-pisa-tuloksista-oppimistulokset-saadaan-nousuun-lisaamalla-opetusta-erityisopetusta-ja-vahvistamalla-opettajamitoitusta/

Author

Minna Niemi

PhD, Principal Lecturer, Social Worker

Social and Health Care Unit

Tampere University of Applied Sciences

minna.niemi@tuni.fi

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5258-9740

Photo: Jonne Renvall / University of Tampere